The jazz bassist and composer Ahmed Abdul-Malik was born Jonathan Tim Jr. in Brownsville, Brooklyn, in 1927. Throughout his life Tim claimed Sudanese descent, but according to the historian Robin D. G. Kelley, his roots were actually Caribbean. In the Fifties it was not unusual for black musicians to search for new connections with their diasporic heritage. As immigrants arrived in American cities in greater numbers, there were more opportunities to discover the religions, languages, and music of Africa and the Middle East. In his book Africa Speaks, America Answers, Kelly describes “a Bedford Stuyvesant renaissance where a transplanted African culture thrived, Islam took root, and the international movement for Afro-Arab solidarity found its American champions.”1

Malik took spiritual inspiration from these surroundings, converting to Islam in his teens and learning Arabic. In high school he joined the Muslim Brotherhood, an offshoot of the Ahmadiyya movement that Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad founded in the Indian subcontinent in 1889. Ahmidayya found American footing in the 1920s, in Detroit, Chicago, and Harlem. It had many adherents among jazz musicians in the late 1950s, including the saxophonist Yusef Lateef, the drummer Art Blakey, and the pianist Ahmad Jamal. (When he converted, Blakey briefly adopted the name Abdullah Ibn Buhaina, and the nickname “Bu” stuck.)

Malik’s study of Middle Eastern culture directly fed his aesthetic ideas. He learned to play the oud—studying off and on with visiting masters from the Arab Music Institute in Cairo—and used Middle Eastern and North African scales and modes in his compositions. Most importantly, as he noted in a 1963 interview, he hoped to create a spiritual music, an art form seeking the “ultimate truth.”

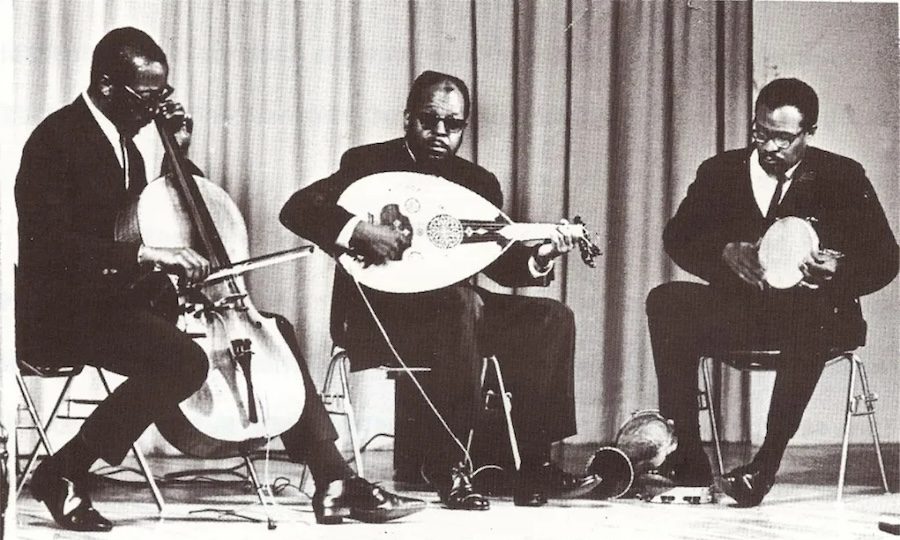

After early success collaborating with the pianists Thelonious Monk and Randy Weston—the latter a childhood friend from Brooklyn who also immersed himself in African music—Malik made his first record as a leader. Jazz Sahara, released in 1958, used the flame of late Fifties hard bop to light the wick of North African folk music. The first track, “Ya Annas (Oh, People),” begins with a solo by the Syrian violinist Naim Karacand, who plays non-Western scales over a simple dance rhythm, before the saxophonist Johnny Griffin swings over a squared two-bar vamp, catapulted forward by Al Harewood’s drumming. Karacand returns with an ecstatic melody, accompanied by Bilal Abdurahman—another Brooklyn neighbor and member of the Brotherhood—on duf or tambourine, Jack Ghanaim on the zither-like qanun, Mike Hamway on a goblet-shaped drum called a darabeka, and Malik himself doubling on the lute-like oud. The piece ends with the leader returning to bass, soloing over a groove that feels only slightly more Khartoum than Brooklyn.

If Jazz Sahara juxtaposes two traditions in a fairly conventional way, The Music of Ahmed Abdul-Malik (1961) takes a more spontaneous approach. Instead of carefully arranging and structuring his tunes around soloists, Malik loosens his compositional authority, allowing the band to use the bare bones of melody, vamp, or rhythm as improvisational jumping-off points. On both albums, however, Malik’s musicians seem refreshed by the limited material. Their playing—whether Harewood’s driving swing or Andrew Cyrille’s more expressionist drumming—has a joy and risk that isn’t found in their other work of the period.

Malik made four more records amalgamating these musical languages. Their titles alone are suggestive: Sounds of Africa (1962), The Eastern Moods of Ahmed Abdul-Malik (1963). Other artists of the time explored a similar fusion. Weston translated North African melodies into solo piano performances; Lateef learned to play reed and percussion instruments from the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. But only Malik placed artists from the Saharan tradition directly alongside New York jazz royalty.

Malik performed as a sideman on commercially successful records by Monk, John Coltrane, and the blues and folk singer Odetta. Unfortunately his own albums didn’t sell. He turned from recording to education, teaching jazz improvisation at NYU into the 1980s. Two strokes cut his life short in 1993, twenty years after his last studio appearance, a 1973 album with Weston.

For a long time it seemed as if Malik was lost to jazz history. In the last decade, however, a European quartet calling themselves أحمد [Ahmed] has revived his legacy to create a new music of their own. The group grew out of ISM, the British pianist Pat Thomas’s trio with the French drummer Antonin Gerbal and the Swedish bassist Joel Grip. In 2015 Thomas invited along a fellow Brit, the saxophonist Seymour Wright, who suggested they study Malik’s oeuvre. The members of the burgeoning quartet all loved his records. Thomas recalled his first encounter in a 2019 article:

Nights On Saturn was one of the recordings that changed my life.… I can honestly say that it still shocks me. It can be compared to Magic City by Sun Ra in how it creates an other-worldly sound: Rahman’s playing on the piri, the shifting, polymetric playing of Cyrille, the free-flowing ostinato bass figure by Malik, and the arco cello playing by Scott.

The other three likely felt similarly. Gerbal, Grip, and Wright each have a history of partnering with freethinking artists: Wright has worked with the Chicago footwork DJ RP Boo, Grip plays with the poet-percussionist Sven Åke Johannson, and Gerbal is close with the French electronics iconoclast Éliane Radigue. These collaborations have made them conversant in different aspects of minimalism: repetition, silence, and the slow metamorphosis of a single idea. Malik’s late compositional aesthetic of “less is more” may have been as alluring to them as the sound of his earlier exotica.

Pieces like “Oud Blues” or “Nights on Saturn” offer very little by way of melody, harmony, and rhythmic information, a feature that informs أحمد [Ahmed]’s mission: “No discussion. No plan. No solos.” This is a radical way to approach historical music, which is often either transcribed, arranged, and presented as a museum piece or treated as a handy bookend for unrelated improvisation. Instead أحمد [Ahmed] uses Malik’s compositions as building blocks for something wholly new. They deconstruct each work into melodic fragments, rhythmic impulses, and broad harmonic motion, twisting small bits of material into fresh structures. Their’s is not a tribute to Malik’s records, but an extension of his experiments. Where he elicited new ideas from musicians of different traditions, أحمد [Ahmed] distills his compositions through a collective education that includes ideas gleaned from diverse sources: Boo, Johannson, Radigue, et al.

After irregularly performing at festivals and small concerts for a few years, the group released its first record, Ahmed New Jazz Imagination, in 2017. They have since released four more albums to increasing critical notice. The group rarely tours but will make long-overdue stops in the US in 2025, in New York and at the Big Ears Festival in Knoxville.

In 2022 أحمد [Ahmed] performed five concerts at Stockholm’s now defunct Edition Festival, and this April the festival’s founder, John Chantler, released the material from their residency on his label Fönstret. (I also performed at the festival and contributed a short essay to the release’s liner notes.) Giant Beauty is a robust box set of five discs—clocking in between forty-five and fifty minutes each—that document the band pushing the recognizable elements of Malik’s music to their limit. Thomas and Grip mushroom and shatter his compositions into raw blasts of noise and percussive harmonies, while the rhythm section swings ridiculously fast for a formidably long time. Malik’s originals are, the critic Lee Rice Epstein writes, “luxuriated in, realized anew, and expanded upon like a wave receding from a shore and echoing back through countless incoming breakers.” But the real achivement of Giant Beauty is that أحمد [Ahmed] detonate Malik’s creations without losing the delicate thread of his vision.

“Oud Blues,” performed on the third night of the festival, is a case in point. On the 1961 recording, the cellist Calo Scott walks a medium-fast blues with Cyrille while Malik dances a joyful bebop lines on the oud for two-plus minutes. That’s it. Its simplicity almost precludes its claim to being a composition. Yet أحمد [Ahmed] makes an entire set-length performance out of it. Grip begins by referencing Scott’s walking line at a slightly faster clip. Wright approximates Cyrille’s high-hat two-and-four with percussive tongue slaps on his saxophone reed. Gerbal softly merges with the groove while Thomas coats the music with thick, colorful harmonies in a dissonant version of the “locked-hand” technique: the way jazz pianists of the 1930s played the melody with the pinky of their right hand while harmonizing it with the other nine fingers. Occasionally Wright leaves off his reed-popping to roar a rude honk that would be comical if it didn’t swing so hard.

At the set’s virtuosic peak, they play four versions of Malik’s blues in four different tempos. Thomas is still deep in the Thirties; Wright stubbornly locks into the shriek of late-Sixties “fire music”; Grip lays down a driving vamp that wouldn’t be out of place in New York jazz clubs today; and Gerbal covers the band in a luminous mid-Fifties hard-bop sheen. This era-hopping is deliberate. In an essay for the Finnish magazine WeJazz, Wright explains that the group undertakes a “deliberate stretching, a study, and a synthesis across several living traditions and communities of practice.”2

أحمد [Ahmed] performed a different Malik tune each night in Stockholm. On the first night’s version of “El Haris (Anxious),” from Jazz Sahara, they use particles of melody to build to an rapturous free jazz climax. On “Nights on Saturn,” from the second night, Thomas and Wright refer to the original melody from The Music of… in different tempos and keys. “African Bossa Nova,” veers from the snaking dance of the Sounds of Africa original to a series of manic repetitions reminiscent of Julius Eastman. And the final night’s “Rooh (The Soul),” from East Meets West (1959), becomes an elegiac, droning tribute to the free-jazz cellist Abdul Wadud, who had passed that day.

The synthesis of ideas is not unusual in jazz; it may be one of its defining features. But Ahmed Abdul-Malik did not add Middle Eastern instruments to his records simply to access a novel sound. His music has a palpable sense of intent: it is searching and unfinished, anxious and exciting, life-affirming and perhaps life-changing. أحمد [Ahmed] honor him by bringing their broad knowledge in and outside the jazz tradition to bear on his compositions—finding their own “ultimate truth.”